Superhuman. What is the definition? What are superhuman abilities? What are 5 examples like genetics, implantable electronics and more. Including benefits, risks, impact & ethics!

What is a Superhuman

What is the superhuman? In previous articles that I’ve written, I’ve discussed closely-related concepts such as human enhancement, longevity and biohacking [link at the bottom]. In essence, it comes down to the following: it’s about using certain therapies or interventions in order to enhance the human body and the quality of life, rather than treating or curing disease.

According to Jos de Mul, professor in Philosophical Anthropology and its History at Erasmus University of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, it can be characterized as follows: ‘It’s not just about increasing our life expectancy. It’s also about enhancing and augmenting our bodies: by means of prosthetics, by connecting the human brain to computers and robots, and by increasing our quality of life through pharmaceutical supplements or neural stimulation.’

That’s why the concept of the superhuman is also closely associated with philosophical movements such as trans- and posthumanism. I’ve previously written a separate article about these movements as well [link at the bottom].

Talk about Superhuman

I gave an online talk about this topic at the Biohackers Assemble 2020 conference. You can watch the video below or on my YouTube channel.

This section zooms in on the definition of the superhuman and how various philosophers view this concept.

Superhuman definition

What’s the definition of a ‘superhuman’ being, exactly? In addition to the description proposed by professor De Mul, there’s another definition that I like, which was put forward in an essay by researchers Ira van Keulen and Rinie van Est [link at the bottom]. Their vision is: ‘We ourselves, as human beings, are an engineering project. An important catalyst for this is the convergence of nanotechnology, biotechnology, information technology and cognitive technology.’ They also refer to this as the ‘intimate-technological revolution’.

We ourselves are an engineering project.

Ira van Keulen and Rinie van Elst, Rathenau Instituut

According to them, the intimate-technological revolution has led to a new wave of technological applications, most of which are intimate technologies that can monitor, analyze and influence our body and our behavior in a variety of ways. I would like to add to this, that intervening in the human body and modifying it, are a part of this as well.

Examples of such technologies include genetics, genetic modification, nanotechnology, biotechnology, synthetic biology, neurotechnology and biohacking. I’ve previously written several individual articles about all of these topics, so take a look at the links at the bottom if you would like to read more about them.

Superhuman Abilities (7x)

For what reason would humans want to ‘upgrade’ themselves? Apart from looking into why we would want to do so (we’ll get to that question later), let’s take a look at the myriad of enhancement options first. I’ve listed them here to provide you with several abilities.

- Cognitive enhancement: boosting your intelligence, increasing your ability to concentrate or enhancing your memory;

- Physical capabilities: having more strength, speed, endurance or mobility;

- Health: living a longer, healthier and pain-free life;

- Emotional: getting better at recognizing and expressing your feelings;

- Morality: having more empathy and compassion;

- Spiritual: having a greater sense of purpose and meaning;

- Sensory perception: having better vision or extra sensory capabilities, e.g. bats and their ability to use echolocation.

I’ve conducted a wide range of personal experiments in order to (try to) enhance myself, experimenting with nearly all of these different categories. To name a few examples: I used nootropics to enhance my concentration skills, tried several different diets to gain muscle strength, I regularly get my blood tested to monitor my health, I used psychedelics for spiritual growth, and I had a chip implanted in my hand to boost my physical capabilities [link at the bottom].

Philosophers on the makeability of humans

How do philosophers look at the makeability of human beings? In a report by the Rathenau Institute, German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk describes how technology enables us to ‘breed’ and ‘tame’ human beings. ‘Taming’ humans entails everything from e-coaching, based on big data and smart algorithms, to seeing personalized advertisements on social media. ‘Breeding’ refers to processes such as embryo modification, which I’ll elaborate on later in this article.

Taming human beings actually isn’t a new or recently-invented concept, but something that has been discussed throughout all of history. Plato (428 – 348 B.C.), for example, believed that children should grow up as bastard children and be raised by a communal crèche. Diplomat Thomas Elyot (1490 – 1546) believed that boys shouldn’t be allowed to be around men during the first 7 years of their life, and shouldn’t be allowed to be in the company of women after they had reached the age of 7. Philosopher Thomas Locke (1632 – 1704) felt that children should be given leaky shoes and that they should stay far away from poetry.

Breeding human beings (i.e.: creating ‘makeable’ humans) has long captured philosophers’ interest as well. ‘What does it mean to be human?’, is a question that already caught the attention of many Greek philosophers in ancient Greece. And according to Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), it’s actually the most important question that we should be asking ourselves. Contemporary philosophers that study this question, are often specialized in bioethics or in human-technology interactions.

According to John Harris, a well-known British professor and philosopher, human enhancement is ‘a beautiful prospect’. Australian professor Julian Savulescu takes it one step further and contends that in their current, non-enhanced form, humans are actually unfit for the future. In a documentary called ‘The Superhuman’ (Dutch), he argues: “We’re morally obliged to enhance the human species. Just to name one example, about 1% of the human population are psychopaths. Why wouldn’t we want to enhance our society, be it physically, cognitively or morally?’

Origins

Professor Peter-Paul Verbeek (a Dutch philosopher of technology) and I recently participated in a podcast series about the ‘bionic’ human. One of the most important ideas that he shared with me, is that human enhancement technologies will gradually start becoming more and more accepted.

Verbeek: ‘I don’t think we’ll suddenly all start wearing a chip or genetically modifying ourselves. Instead, we’ll see certain technologies that were previously only used for medical purposes, transition into being utilized for ‘normal’ use. That’s what we’re currently seeing with Ritalin and plastic surgery as well.’

I personally agree with this point of view. One hypothetical example is a medication that can help heart disease patients by protecting them from a heart attack, but that can also be used to increase the life expectancy of ‘normal’, healthy people. It’s quite likely that everyone would want to start using that medication. This is currently happening with other medicine as well; students are using beta blockers before their exams, and the use of Viagra is no longer limited to medical purposes either.

Superhero science

What is the science behind superhero technologies, like Iron Man’s suit? On my English YouTube Channel I interviewed author and science communicator dr. Barry Fitzgerald.

How can we change or modify humans? What different types of modification are there?

Examples (5x)

So how do you produce a ‘makeable’ human? In a previous article about superhumans, I made a distinction between mechanical, medical, genetic and pharmaceutical modifications [link at the bottom]. I’ve made a short summary of these different types of modifications:

- Mechanical, e.g. augmenting the body with electronics or exoskeletons;

- Medical, e.g. artificial blood substitutes or artificial retinas;

- Genetic, e.g. modifying the DNA of an embryo/human (more about this later on);

- Pharmaceutical, e.g. using Modafinil for increased focus and attention.

The purpose that these different forms of human enhancement were originally used for and that they emerged out of, varies. As professor Verbeek mentioned, they often stem from medical substances or therapies. Another useful source for human enhancement techniques is the army. For instance, the American army created a Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit (TALOS) to increase their soldiers’ strength and to make them less vulnerable.

Apart from these four types of modifications, concerning fully-grown human beings, modern-day technology also enables us to modify humans before they are even born. The next section of this article zooms in on that development.

What about human reproduction? That’s what the next section will dive into.

Creating makeable humans

How can you create – or in Sloterdijk’s words, ‘breed’ – makeable humans? The first step towards this was the invention of IVF. The first IVF-baby, whose name is Louise Brown, was born in 1978. IVF refers to in vitro fertilization, a method that produces what is also known as ‘test tube babies’. When IVF was first introduced, it sparked a lot of controversy and discussion. Nowadays, however, it is completely socially accepted. In fact, 1 in 30 kids are born through IVF these days.

PGD, preimplantation genetic diagnosis, takes things one step further than IVF. PGD is the genetic profiling of embryos prior to implantation, in order to find genetic abnormalities. Embryos that don’t display any genetic abnormalities during this screening, are then placed in the womb.

Designer baby

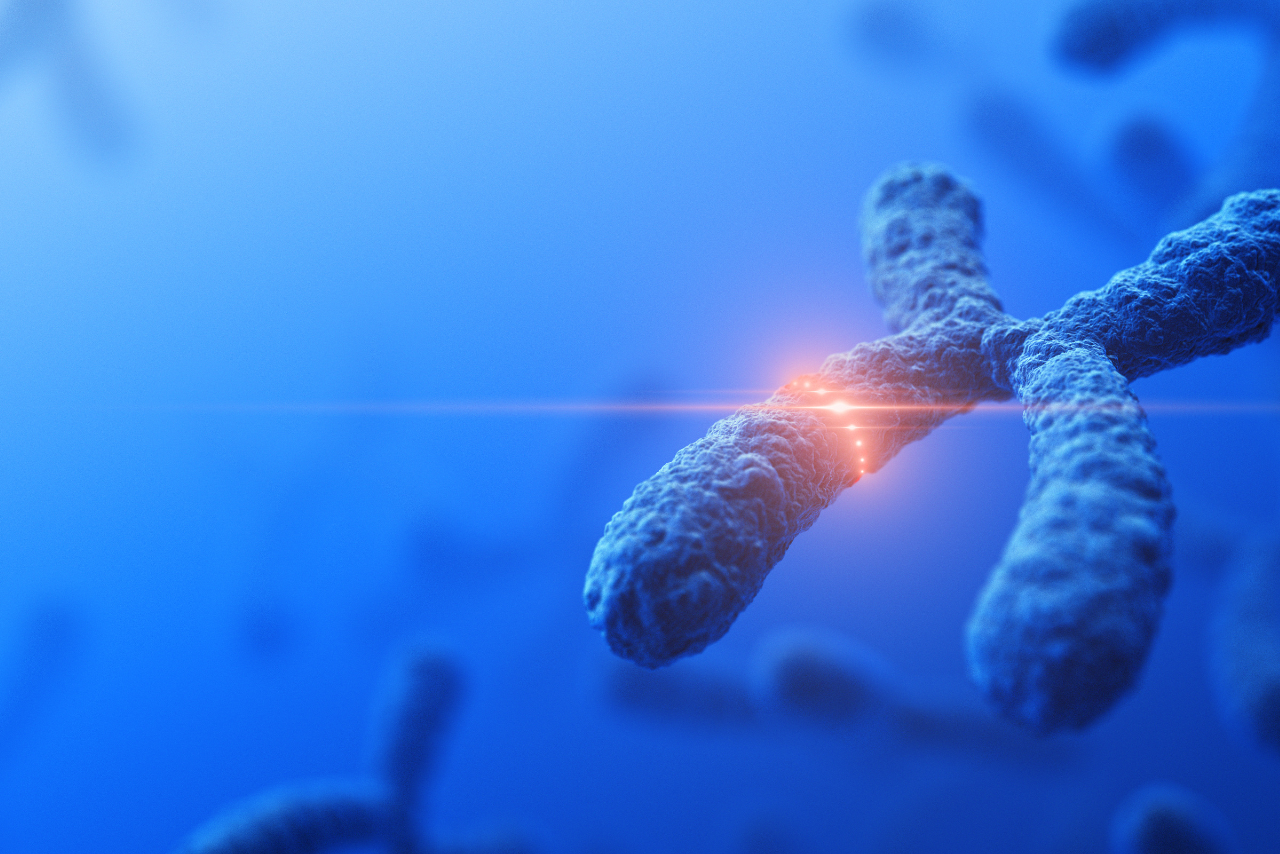

One scientific breakthrough that could enable us to really start ‘making’ or ‘engineering’ people, is CRISPR/Cas9 [link at the bottom]. This technique can be used to modify our genes. Genes, or DNA, are the ‘building blocks’ of life. They determine the growth, maintenance and demolition of our cells and other biological processes in the body.

A controversial application of this technique, is to modify genes in the early stages of the development of an embryo; for instance, in a tube, right after the egg has been fertilized by a sperm cell. This could help prevent genetic diseases, but it could also change certain personal characteristics – for instance, having a better immune system, higher intelligence or more muscle strength.

This type of modification is also known as germline engineering, and the consequences of these modifications are permanent. That means that they are also passed on to future generations.

- Ukraine. Ukraine allows a certain treatment where mitochondria are transferred to a different egg cell. Theoretically, this counters cellular aging, which could help older women conceive more easily. In the UK, this treatment (mitochondrial replacement) has been approved for use for various mitochondrial diseases.

- Cyprus. An IVF clinic in Cyprus allows parents to select their embryo’s sex. They do this in the context of ‘family balancing’, i.e. if you’re a parent of two girls and you would like to have a boy.

- India. Commercial surrogacy is quite widespread in India, with multiple clinics providing commercial surrogates. An article by The Guardian asserts that Indian women can earn about £4.500 for being a surrogate. That’s a very large amount of money, considering that the average monthly salary in India is about £215.

Methods

The Netherlands has strict legislation in place when it comes to applying such techniques. Other countries have less stringent legislation, so people who are interested in genetic modification often travel to specific countries that offer a broader range of possibilities. Sjoerd Repping (professor in human reproductive medicine at Amsterdam University Medical Center): “Humans have an intrinsic drive to reproduce and survive. The desire to produce offspring is incredibly strong. If the technique is there, there’s a market for it.” To name a few examples of countries with different laws and regulations:

Reproduction 2.0

Do you actually still need a man and a woman to produce a child? In 2018, researchers of Maastricht University and the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht reported that they had managed to produce mini-embryos from mouse stem cells [link at the bottom].

Perhaps, in the future it will be possible for two men to conceive a child together. Or for women to have a child without a donor. The egg cells would then be fertilized with sperm produced from their own stem cells.

In this scenario, the embryo would be produced in a laboratory and develop into a baby through ectogenesis. As such, women would no longer have to carry a baby for 9 months [link at the bottom]. This might seem strange to us now, but it could be completely normal in 25 years from now.

A short overview of the reproductive techniques I discussed:

- IVF (in vitro fertilization): the egg is fertilized in a test tube, after which it is placed in the womb;

- PGD (preimplantation genetic diagnosis): DNA screening of an embryo;

- Germline engineering: DNA modification of an embryo;

- Ectogenesis: the development of an embryo into a baby, outside of the body.

As you can probably tell, science is moving at a rapid pace and is able to influence more and more aspects of the reproductive process. That makes the question of whether we want to proceed with this – and if so, how, and for whom – all the more relevant. That’s why there’s been an upsurge in attention for the bioethical implications of this as well.

Ethics makeable human

The advent of a new technique or technology practically always raises questions about its safety and effectiveness. When it comes to techniques such as IVF or PGD, these were generally only meant to serve a strictly medical purpose. But once the technology is there, it often generates new wants and needs outside of the original realm.

Critics are worried that this might be a slippery slope: when do we consider something a medical ailment or disease, and when do we consider it human enhancement? How far do we want to go when it comes to producing designer babies.

It’s important that we start having ethical discussions about where we should draw the line

Jeantine Lunshof (MIT Boston)

In an interview Jeantine Lunshof (MIT Boston) stated that there’s no way of halting the development of the techniques themselves: ‘At most, we’ll be able to prohibit specific applications of these techniques. It’s important that we start having ethical discussions about where we should draw the line.’

Line between medical and non-medical

Philosopher Mertes (Ghent University) also acknowledges that it’s a tough discussion: ‘It’s not at all controversial to cure an embryo when there’s a serious medical issue involved, but when the same technique is used for a different purpose, it generally is controversial. However, the line between medical and non-medical interventions isn’t always so clear-cut. Intelligence, for instance, currently isn’t deemed an acceptable intervention criterion. But what if it turns out that an embryo has a far below average level of intelligence? Wouldn’t we be tempted to boost its intelligence? We need to be careful that we won’t shift the intervention criteria towards trivial characteristics.’

Annelien Bredenoord is an assistant professor in Bioethics at Utrecht University: ‘We’ve always considered it irresponsible to modify genes on a germline level, because those modifications will be passed on to future generations.’

However, in 2015, the British parliament approved of a new application of the technique. It is now legally allowed to replace the diseased mitochondria of an embryo with healthy mitochondria. That way, a child and its offspring are forever cured from their mitochondrial abnormalities. Should we really consider something like that ‘irresponsible’?

Epigenetic programming

I talked about this in a podcast interview with Désirée Goubert, PhD candidate in Epigenetic Editing. Désirée thinks that epigenetic programming definitely has potential, but there are a lot of political and ethical hurdles that need to be cleared first: ‘Do we really want to move towards the ‘makeable’ human, and modify characteristics like the eye color or the intelligence of our future designer babies? Or do we want to limit the use of these techniques to extraordinary circumstances or diseases, such as the BRCA1 gene, which increases the risk of breast cancer.’

Personally, I believe using epigenetic programming to cure certain diseases is a good thing, but I think we need to be very careful when it comes to changing aesthetic traits such as eye color, or our intelligence levels. We shouldn’t want to move towards a world in which everyone has the same genetic characteristics. Just one virus would pose a serious threat, in such a scenario, and we would all be equally vulnerable.

Pace

Both Sjoerd Repping and Heide Mertes emphasize that we shouldn’t exaggerate our expectations about the pace at which reproductive technologies are moving. Heidi Mertes: ‘Generally, technology doesn’t develop as rapidly as people think. We won’t suddenly have a world full of designer babies when we wake up tomorrow.’

This section addresses the consequences of the Superhuman

Why would we want Superhumans?

The desire to ‘upgrade’ ourselves might sound like a very modern-day concept. In reality, however, it’s something that has always captured our interest. In 1943, British author C.S. Lewis published the book The Abolition of Man. Much later, he also wrote the popular book series The Chronicles of Narnia.

In his book The Abolition of Man, Lewis explores the question: what if our power over nature grows, and thus our power over mankind?

In Lewis’ eyes, those who use such techniques don’t actually possess their own, individual power over nature. In an article in De Groene Amsterdammer, Frank Mulder puts it as follows: ‘It’s a power that certain people possess, which they can choose to let other people benefit from as well.’ Take an airplane, for instance: you can use it go on holiday, but it can also be used to bomb people.

Consequences makeable human

What kind of consequences could this have? How should we, as humans, move forward? What happens when we have so many powerful resources at our disposal, like genetics, genetic modification, neurotechnology and artificial intelligence? C.S. Lewis isn’t too optimistic about this: ‘At the moment, then, of Man’s victory over Nature, we find the whole human race subjected to some individual men, and those individuals subjected to that in themselves which is purely ‘natural’ — to their irrational impulses.’

Lewis wrote about these ‘irrational impulses’ in the time of Nazi-Germany, but what do they mean in our current society? The makeability or genetic engineering of humans is often associated with eugenics. This refers to modifying entire genetic groups of the human population at one’s own deliberation – something Hitler is known to have advocated.

The difference between the present and the early 20th century, is that eugenics comes down to much more of an individual choice now, rather than a collective choice imposed by those in power. However, that doesn’t make the consequences any less positive or negative, because individual choices are influenced by culture, corporations and the government as well.

Consequences for individuals

What kind of consequences does ‘makeability’ bring forth for individuals? In their essay on intimate technology, Van Keulen and Van Est argue that technology is affecting changing which skills we possess. On the one hand we’re learning new skills (reskilling or upskilling), but on the other hand we’re also becoming less competent in other skills (deskilling).

According to the authors, this also has implications for how we interact with each other. Take smartphones, for example. The smartphone has definitely changed the way I communicate and interact with my family, friends and partner.

That’s why Allenby and Sarewitz argue that we should analyze new technologies at three different levels:

- The direct impact of technology on an individual;

- The impact on socio-technical systems and the social and cultural patterns behind these systems;

- The impact on a global level.

If we look at this line of reasoning, we can see that on the surface, human enhancement might seem like it’s solely an individual choice (level 1). But the use of this technology is often driven by commercial, military or governmental interests (level 2). In his book Homo Deus, Yuval Noah Harari also discusses the emergence of a gap or inequality between ‘normal’ humans and superhumans (level 3).

What does the future of the superhuman look like?

The future

According to philosopher John Harris, the ‘makeable’ human is ‘a beautiful prospect’. In an interview with de Volkskrant, he refuted several practical objections [link at the bottom]. To name two examples:

- Natural genomes are not inherently better than manipulated genomes. The only real difference is the ‘ew’ factor, our aversion towards it;

- You have to start somewhere, when it comes to innovations. Wider availability tends to follow anyway.

What’s interesting about his vision, is his idea that makeable humans aren’t going to suddenly appear overnight. ‘Where was the dividing line between apes and humans? It’s impossible to say. The transition from our current form to our future descendants, will be just as seamless.’

The transition from our current form to our future descendants, will be just as seamless as the transition from apes to humans.

John Harriss, scholar and author

We’ve already seen the first steps towards this. Back in 1991, Mark Weiser, who was the chief technologist at Xerox, stated: ‘The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.’ His vision fully concurs with the concept of the makeable human. By adding technology to our bodies or by using technology to modify ourselves, we will no longer be able to distinguish the use of intimate technology from who we are as humans.

Humans playing God

What could this lead to? According to Yuval Noah Harari, author of the book Homo Deus, scientists are turning us into gods instead of humans. They’re not doing that on purpose. They’re working on treatments and therapies meant to cure diseases, and as I discussed before: some of these medical treatments could also be used in ways that could help healthy people augment their skills or live a longer life.

In his book, Harari argues that humans consist of ‘algorithms’ made out of feelings, emotions and desires. Thanks to scientific breakthroughs, scientists have gotten better and better at analyzing and steering these ‘human algorithms’.

Our subjective experiences consist of feelings, emotions and thoughts that are connected to each other. Our thoughts and memory are composed of electrical signals that neurons transmit to one another. Some scientists, such as Daniel Dennet and Stanislas Dehaene, believe that all relevant questions concerning the ‘human algorithm’ can be answered by analyzing our brain activity. In their opinion, consciousness or subjective experiences don’t play any role in this.

Dangers of humanism

Thanks to science and technology, we’re able to analyze and manipulate the behavior, feelings and preferences of human beings better than ever before. At the same time, we still live in a very humanism-centered world. That means that we, as humans, give meaning to the world around us and that the individual is our priority. Consider politics (the voter decides), the economy (the market decides), art (beauty is determined by the observer) and education (students need to think for themselves).

But, as we’ve also discussed before, scientists, corporations and governments are getting better at analyzing and manipulating human feelings, thoughts, preferences and our desires. On a different level, Harari refers to this as dataism. This notion assumes that data can solve anything. Humans, in their role as ‘human algorithms’, can be seen as a data processing system. In fact: we contribute to so-called dataism through the use of email, social media and Internet of Things devices. All of this data ends up in the hands of big corporations like Google, Facebook en Amazon.

To what extent will we determine what the future of humanity looks like?

In my opinion, this is the crux of the matter. What if you take earlier warnings about makeable humans and juxtapose them with these developments? If the primary driving factors behind human enhancement are of an economic and political nature, and if these powers continue to get better at manipulating our behavior, to what extent will we as individuals or as members of society be able to influence the future of humanity? There is a real risk that we’ll get the illusion that we’re able to do so, but that we won’t actually be in control of our own fate.

Impact on society

Another scenario that Harari comes up with in Homo Deus, is the fact that the makeability of humans could split humanity into two different classes: a class of ‘normal’ people, and a class of ‘superhumans’. Professor Michael Bess, author of a book called Make Way for the Superhumans, also believes that this poses a threat. In his opinion, there’s actually an additional form of fragmentation that could occur [link to my interview with Michael Bess at the bottom].

Michael Bess: ‘In addition to vertical fragmentation, there could also be a risk of horizontal fragmentation. There’ll be clusters of people with a certain form of enhancement. Imagine musicians modifying themselves in certain ways and clustering together. They will no longer mingle with other groups, like tennis players or runners. Given that we tribal inclinations are a big part of who we are as humans, that could create tension between different parts of the population.’

Solution

The opportunities that we’ll have at our disposal in the future, to create ‘perfect’ or ‘makeable’ humans, also come with a large number of responsibilities. They can lead to a better world, but they could also lead to a dystopian society. According to Michael Bess, it’s up to us to make that decision, through both our individual and our collective choices.

Collective choices refer to the rules and agreements we need to make about the development and use of new technologies. One simple rule could be that you’re not allowed to have any upgrades that could cause harm for others. However, oftentimes, it’s nearly impossible to predict or foresee the eventual consequences of a new technology. I wrote about this more in-depth in an article about technology ethics [link at the bottom].

A good example of this is a patient who suffered from Parkinson’s disease. He underwent a Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) treatment, a technique that sends electrodes to certain brain areas to counter the symptoms of this disease. It worked, but it also changed the patient’s personality. He suddenly became an extravert, and started buying expensive things, stealing and cheating. There was no middle ground: after the DBS treatment, these effects disappeared again.

Individual choices have to do with deciding what your core values in life are, as an individual. You probably won’t be able to get all the upgrades that are available, so you’ll have to be selective and consider the pros and cons, the impact on others, and the potential implications. As a fictional example: you might be able to get a certain brain implantation which allows you to focus better, but you won’t be able to get an enhancement for your motor skills as well.

Apart from the philosophers and ethicists that I’ve already discussed, there are also plenty of artists, directors and documentary film-makers that are interested in this topic.

Superhuman documentary

Netflix has several interesting episodes on a various aspects of human enhancement. One episode of a show called Liquid Science is about longevity, and there’s one episode of Explained about the genetic modification of embryos.

In 2013, a documentary called Fixed: The Science/Fiction of human enhancement was released [link at the bottom]. This documentary is available for a few dollars.

Movies

What are some interesting movies about the makeable human? The movie Gattaca (1997) is a classic when it comes to embryo selection and modification. Most parents in the movie opt to outsource reproduction to one of the clinics.

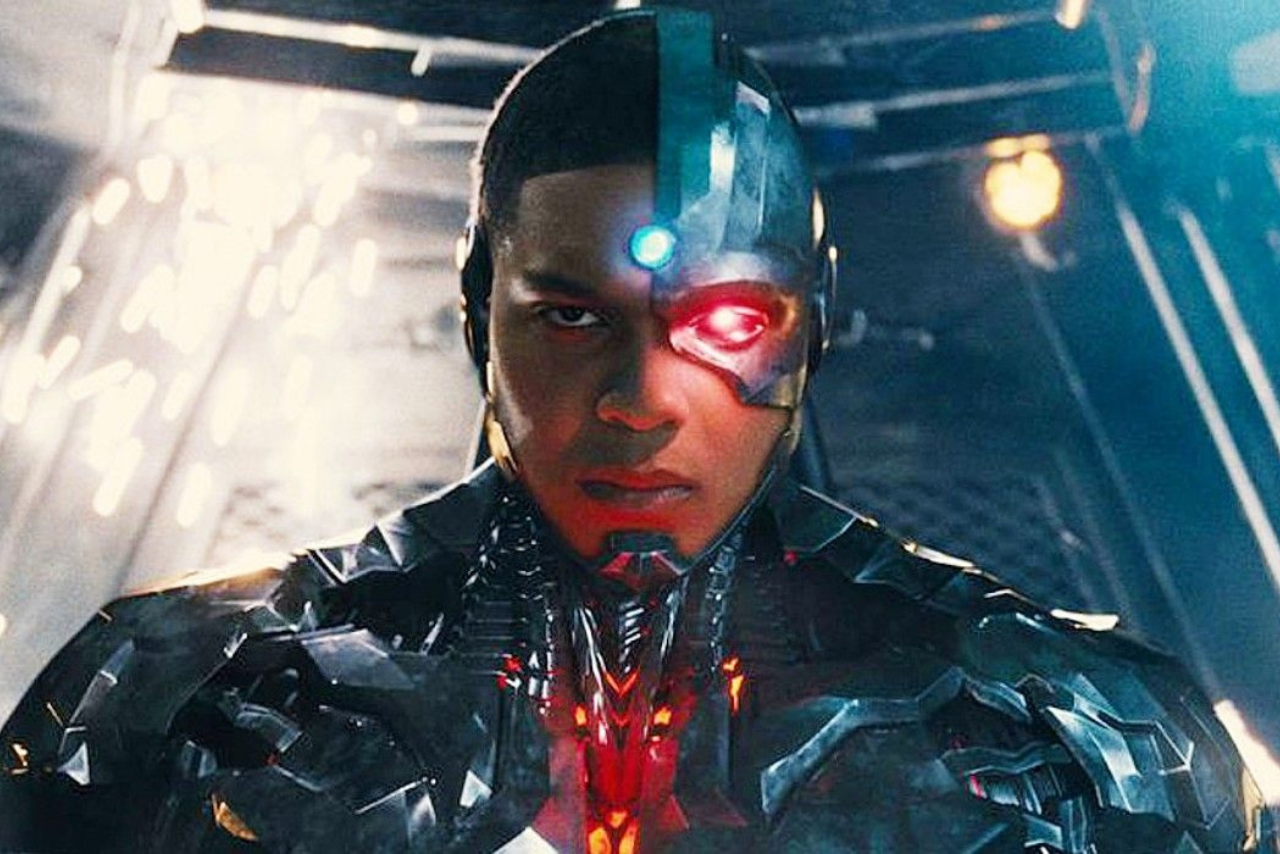

The original movie Ghost in the Shell (1995) is about a cyborg; an organism that is part human, part machine. The only body part that isn’t artificial, is her brain – the rest of her body consists of mechanics and synthetic organs and tissue. Are you still a human being in these conditions? Do you ‘own’ those modifications? In 2017 the original manga was made into a Hollywood blockbuster with Scarlett Johannson.

An interesting movie about longevity and its implications is In Time (2001). In this movie, the biological aging process is brought to a halt when the characters turn 25. It’s an interesting thought experiment about the kind of rules and agreements that we would have to make as a society, when it comes to longevity. Would we have to come to an agreement about how much time people are allowed to spend on earth? Could you buy more time if you had the money?

TV shows

What are some intriguing TV shows about the makeable human? The Jetsons (1962) is a comical animated TV series about a family that lives 100 years into the future. Professor Michael Bess discusses the show for a different reason, however, having come up with the ‘Jetson Fallacy’. His idea is to illustrate that a lot of science fiction movies or TV shows miss a key element.

Although the world itself has changed significantly in the show, with flying cars and housekeeping robots, humans haven’t. According to Michael Bess, it’s inevitable that we ourselves, as humans, are going to change as well.

One of my favorite TV shows about the future is Black Mirror (2011). You can watch this show on Netflix. A few episodes that explore the ‘makeable human’ theme, are: The Entire History of You (season 1) about enhancing your memory, White Christmas (season 2) about AI simulations and Arkangel (season 4) about having chips implanted in your children, to track and monitor them.

In a Volkskrant interview, Peter-Paul Verbeek also mentioned that he was a fan of the show [link at the bottom]. ‘It seems like Black Mirror is systematically working through all of the big questions that the current technological developments are raising.’

A third personal favorite of mine is Altered Carbon (2018). In this show, the personalities of the characters are separated from their physical bodies. As a consequence, people constantly replace their old body with a new (or cloned) version of it. This produces social inequality.

Books

What are some interesting books or novels about the makeable human? In a podcast for BNR, Peter-Paul Verbeek stated that Frankenstein (1817) is one of his favorites, as it provides us with the lesson that we, as humans, need to educate the technologies we create.

Brave New World (1932) is also an important classic. This book paints a picture of a world that is dominated by technology and rationalization. There’s no poverty or war, but there aren’t any cultural endeavors such as religion or art either.

One book that I really enjoyed reading is Nexus (2012) by Ramez Naam. It’s part one of a trilogy, and it’s set in 2040. The main theme is the discovery of a synthetic drug that allows you to reprogram your brain and link mind to mind.

Another recent example is Seveneves (2015), by famous sci-fi author Neil Stephenson. There’s one concept in particular, which is covered in part 2, that I think is really interesting. In this part, a group of women who are left behind, decide to allow one type of genetic modification per person. The consequence: several generations later, various genetically formed enclaves emerge.

Art

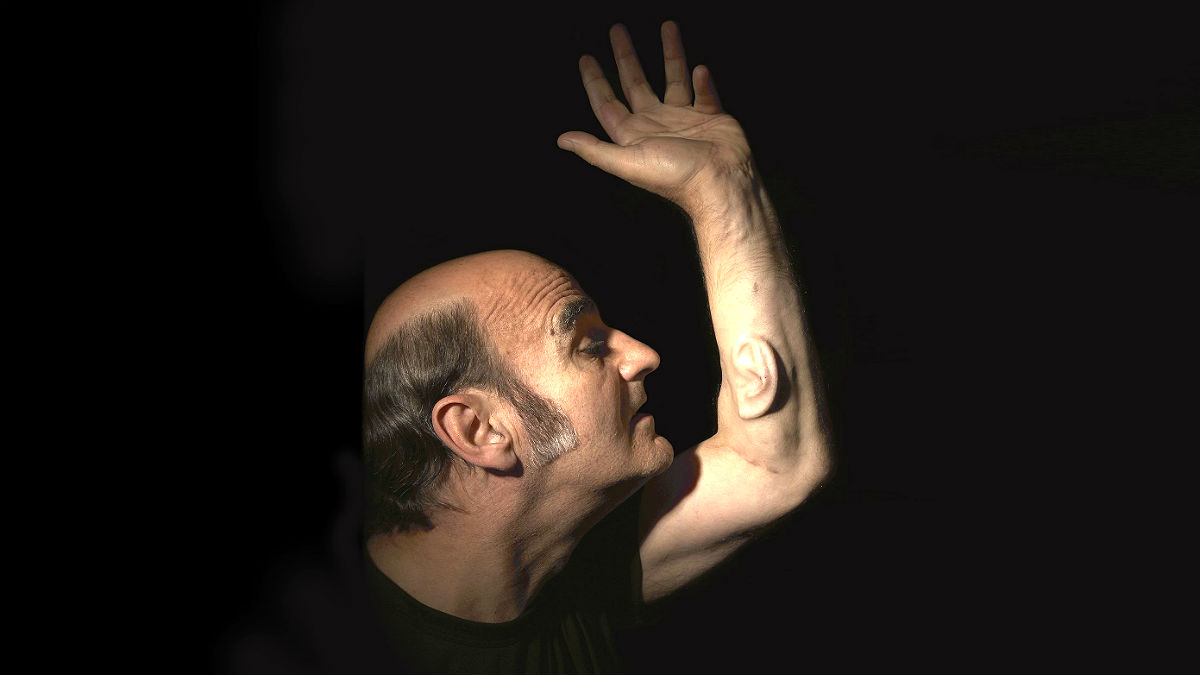

What are the most compelling examples when it comes to art about the makeable human? Naturally, I’ll have to start with Stelarc (1946). He is a performance artist, who has also been called the ‘guru of cyborg art’. He does performances with robots and exoskeletons, and he’s had a so-called ‘third ear’ implanted in his left arm.

At the Brave New World 2017 congress, I met Lucy McRae. She’s a science-fiction artist who refers to herself as a ‘body architect’. For instance, she’s created an electronic tattoo and a swallowable perfume (which is then emitted through your pores).

In the Netherlands, film maker Floris Kaayk (1982) is known for a project called The Modular Body. This is an interactive movie about the makeability of the modular human body. The concept is simple: why do we take humans in our current form as a given? Why wouldn’t we be able to completely redesign them?

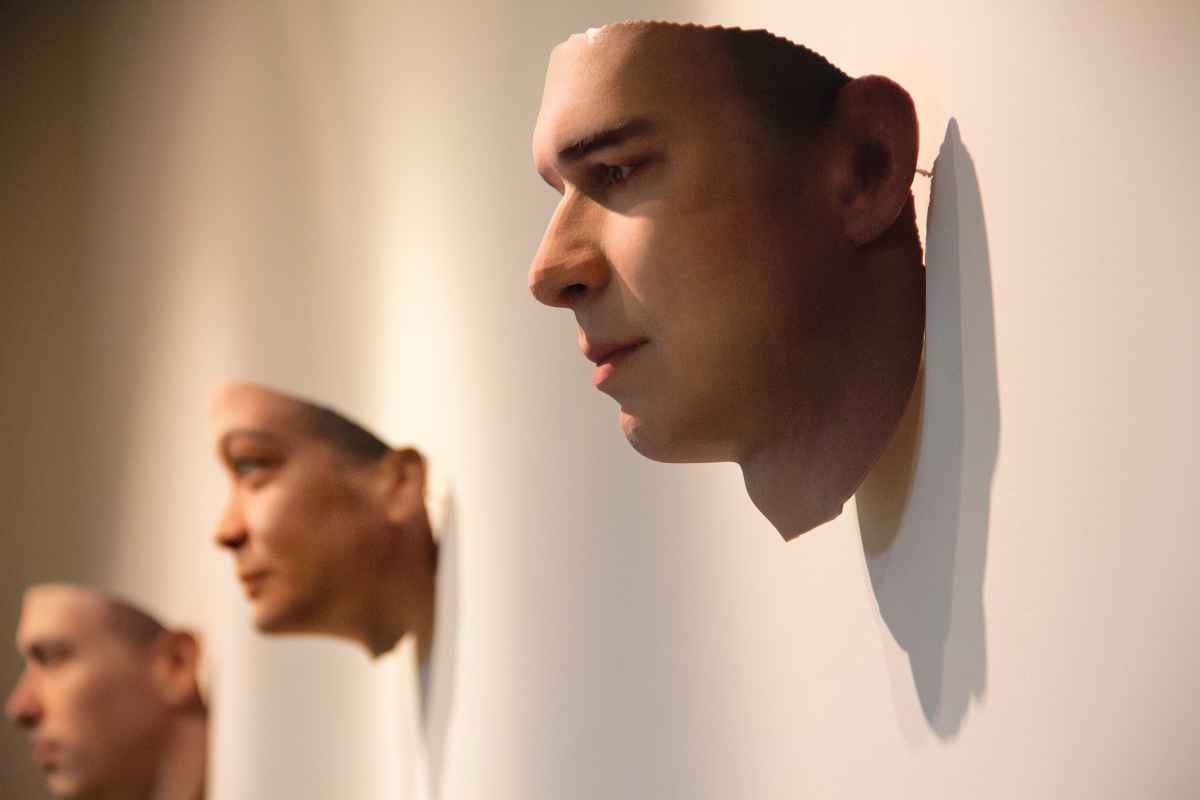

Someone else who’s captured my interest is Heather Dewey-Hagborg (1982). I saw some of her work at Border Sessions 2016 in The Hague, where she also gave a presentation. She creates facial visualizations of people, based on DNA that she collects in public spaces or on the street. Think of a piece of chewing gum, or the butt of a cigarette, for instance. This artwork also got me to reflect on (genetic) privacy and on who owns our DNA.

What’s my conclusion thus far?

Conclusion

In my interview with professor Michael Bess, I asked him whether the emergence of the ‘superhuman’ is inevitable. Chuckling, he said: ‘If there’s one thing I’ve learned from history, it’s that nothing is ever set in stone or inevitable.’

My personal conclusion, however, is that eventually there will be ‘superhumans’. This conclusion is based on a principle that I like to apply when I think about the future. I was introduced to it through Tim O’Reilly’s work. It’s a principle that is encapsulated in a quote by science-fiction author William Gibson: ‘The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.’

The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed

William Gibson, author

My fascination with the future started off with biohacking: using biological, technological and other interventions for human enhancement purposes [link at the bottom]. And all of my personal experiments, as well as interviews with scientists, experts, artists and visionaries, have reinforced my vision that with time, we’ll want to intervene and enhance human beings in more and more radical ways. This might not be too visible yet in our current world, or equally distributed for that matter, but it’s inevitable that humans will do so.

Cautious optimism

Does that idea scare me? No, I’m cautiously optimistic about how we, as humans, will be able to deal with our new skills and capabilities. The phrase ‘cautious optimism’ was also used by A.I. researcher Erik Brynjolfsson to describe how we should approach these changes.

Apart from an unconditionally positive type of optimism, like the expectation that the sun will rise again tomorrow, there’s also, as he calls it, a sort of ‘cautious optimism’. This refers to the expectation that good things will happen, if you work hard enough to achieve them, with care and with a sense of purpose.

That’s the kind of optimism that I feel when it comes to the future of humankind. The question does remain, however, whether our human values and qualities can keep up with the explosive growth of our cognitive and physical capabilities.

Speaker Superhuman

Companies, organizations, and institutions regularly invite me to give keynotes and webinars about the superhuman era. You can find several examples below.

Elevate Talks at the Breda Photo Festival (2018):

The Biohacker Summit in Stockholm (2018):

Reading list

I’ve previously written the following articles related to this topic:

- What is human enhancement?

- What is transhumanism?

- What is biohacking?

- What are cyborgs?

I’ve read the following non-fiction books on this topic:

I’ve also watched the following documentaries on this theme:

- Documentary Fixed

These TV shows, movies, books and artists are related to the concept of the superhuman:

- Movie Gattaca

- Movie Ghost in the Shell

- Movie In Time

- TV show The Jetsons

- TV show Black Mirror

- TV show Altered Carbon

- Book Frankenstein

- Book Brave New World

- Book Nexus

- Book Seveneves

- Artist Stellarc

- Artist Lucy McRae

- Artist Floris Kaayk

- Artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg

These are the external links that I’ve used:

- Essay Rathenau Institute

- Website Julian Savalescu

- Website John Harris

- Research about stem cells in embryos

- Article about ectogenesis

- Article about commercial surrogacy in India

- Article Mark Weiser

How do you feel about the concept of superhumans? Do you want to have superhuman abilities?

Leave a comment!

It is suggested that there is a relationship between the fall of a society and the perfection of mankind. Many economic, social and environmental factors, which all contribute to the sustainability of a society, are built upon the need for a solution to a problem. Superhumanism requires the ability to overcome these problems, either through physical, mental or emotional triumphs of purity and self-actualization. Through the elimination of these problems, many economies and social structures would be collapsed. Also, through advancement in areas such as Transhumanism, some believe that people humans will advance to a point of education and readiness that war will break out between one another, or tyrannies will reign, due to the high levels of advancements being achieved hence correlating with a need for power, eventually leading to an ultimate state of anarchy.

I have a super human ability that 3 out 10 people notice ask people what do they see it’s just video of my arm it has the ability to surveillance other locations I’ve had my skin checked and a mental evaluation it’s 100%authentic

“I have multiple Superhuman abilities more than 1000 people notice my superhuman abilities ( Fernando Udtujan *** 619.514.5588

Fernando Udtujan AKA PINOY SAMSON VS Dwayne Johnson or Manny Pac-Man….( 619.514.5588 Do you want to see me live in action please call me or get all the media too, come to San Diego California U S A.